When the light began to give out, and dusk fell upon them, the sound of guns became more sporadic until – at last – night shadows crept down the hills to their encampment. The raw energy of that first day’s engagement at Gettysburg was slow to wane and few men could call the break restful. In the dark after the second full day, Charles settled himself on the ground and fatigue overtook him.

They had withdrawn to the Baltimore pike and stopped near the cemetery, but only after it was determined that the enemy was in retreat. A light rain began to fall, refreshing those few who remained awake while soaking those slumbering under the sky.

He was twenty years old – Charles Kennard of Portland – serving as a craftsman in the Fifth Maine Battery. Earlier in the day, the unit’s captain had been carried from the field, shot through both legs below the knees. The battery was defending Culp’s Hill against a full-scale onslaught by Brigadeer General Harry Hays and his Louisiana Tigers. Before dawn, Charles was jolted from his sleep by the roar of cannons.

Already, Confederate troops were pushing up the slopes of Culp’s Hill, and Charles and the Fifth Maine jumped into action. Twenty guns in all were set at a range of six to eight hundred yards and the cannonade rained continuously until ten in the morning. It was July 3, 1863 and it was a turning point in the War of the Rebellion.

Young Kennard might have agreed with the sentiment of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, who declared it fortunate that war is so terrible, lest men begin to like it too much. Charles, like many of the Kennard men, was skilled with his hands and he longed to return to the Portland forge – a place far removed from the Gettysburg battlefield.

The Fifth Maine faced more than twelve thousand infantrymen in the assault on the third day. More than forty-five thousand men lost their lives over the course of those three days. Kenneth was among the fortunate ones.

After Gettysburg, after Bull Run, after Fredericksburg, and after the Fifth Maine mustered out at last, Charles O. Kennard made his way back to Portland and the anvil at his forge. He met Josephine, some four years his junior, and in late 1869 he asked for her hand in marriage.

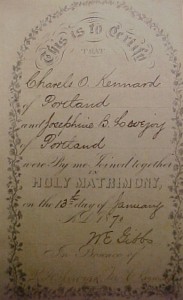

They were married in the new year with W. E. Gibbs presiding and inscribing his name in a small keepsake book presented to the couple. Just before the title page is a specially inscribed leaf that reads, “This is to certify that Charles O. Kennard of Portland and Josephine B Lovejoy of Portland were by me joined together in Holy Matrimony on the 13th day of January, AD 1870.

There are more than 1,400 Civil War soldiers buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Portland, Maine, and Charles O. Kennard is among them. The records of his unit during the war are as well-kept as the grounds of that cemetery.

But there is no record of how the gilt-edged, buckram-bound record of his marriage nearly 150 years ago wound up in a book store in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. You’d think in an age of social media that somewhere out there could be found a great-grandchild, or a great-great – who might value such a keepsake.

I gave it a shot – found a decade old posting on a genealogy website that mentioned Charles – but so far, no response.

And now, the little volume concludes – “And now, young and happy pair, having given you such hints and counsels as I thought expedient and necessary to your happiness, I wish you adieu!”

Come visit!

McHuston

Booksellers & Irish Bistro

Rose District

122 South Main St. Broken Arrow OK!