Dad and son came in to look around.

“Hmmm,” said Dad. “A bookstore.” He didn’t sound optimistic, but came in anyway.

His son might have been nine or ten years old. Certainly old enough to read and tall enough to see over the edge of the counter, where a doll-sized figure was displayed in a clear plastic card-backed package.

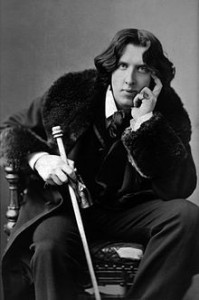

“Dad,” he called out. “Who is Oscar, Wild…Will-dee?”

“Uh-oh,” I thought. “This could be an awkward moment.”

I was remembering the scandals associated with Oscar Wilde (his name has an E at the end, which is – I suppose – why the young man read it as will-dee).

Even as the dad was considering his answer, I recalled putting a similar question to my mother.

“Mom,” I called out. “Who is Bridget Bardot?” Her name must have been mentioned on the television, that big clunky piece of furniture in our living room that displayed only black and white pictures. Maybe I saw a black and white version of Bridget Bardot that piqued my interest.

My mother didn’t hesitate in her reply.

“A movie star,” she said. “She likes to run around wearing nothing but a bath towel.”

I guess the answer worked well enough. I got the idea.

With the young man’s question posed in the book shop, I waited to hear the father’s answer. Finally, he sighed and admitted, “I have noooo idea.”

“He was an 1800s English writer,” I offered, trying to help out the dad. The kid was quick.

“Then why does that say ‘Action Figure?”

“It’s kind of a joke,” I responded. “He wasn’t known for X-Men kind of action.”

When Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde died in 1900, he was destitute and living in Paris. A victim of a scandal of his own creation.

He objected to something that was alleged to have been said about him by John Douglas, the Marquess of Queensbury. It was whisperings (some not so quiet) about Wilde and the son of the Marquess, Lord Alfred Douglas. Wilde sued for slander. In the course of the trial, enough mud was dragged into court concerning Wilde’s antics that he dropped the slander suit. It was too late, though. Wilde was charged with “gross indecencies,” convicted, and sentenced to two years of hard labor. He spent time in jail, although he spelled it gaol. He might have had better fortune in our current society, but in 1890s London there were some things best kept out of conversation.

In his day, Oscar Wilde was one of the most famous personalities around. He was born into a wealthy intellectual family, was well educated, known for his quick wit, and in 1890 authored a popular story called The Picture of Dorian Gray. It didn’t help the author during his lifetime, but when moving pictures were invented it was one of the early books adapted to film. It has been redone several times since that first Hungarian version in 1918.

Wilde had the intellect and wit of Dick Cavett, the social circles of Oprah Winfrey, the theatrical following of Neil Simon, and a wife as influential in her day as Hillary Clinton (well, maybe that last one is a stretch…).

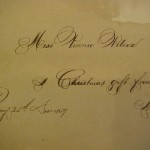

Dapper-looking as he is, I thought Oscar the action figure would be gone by now, landing under some lucky literary Christmas tree. His action figure comrade Charles Dickens found himself a home over the holidays.

But then again – he was more will-dee than Wilde.