Ray J. was just a teenager when the bombs fell at Pearl Harbor. He was tall and thin – in fact, he couldn’t meet the weight requirement at the recruiting office. They sent him home to eat some bananas. When he showed back up, they accepted him into the US Navy and sent him to the Pacific.

He never spoke to me much about his experiences beyond mentioning being a little nervous sitting up in the conning tower when Japanese Zeros passed low overhead. Late in the war, some of the pilots were slamming their planes into the US ships.

On July 5, 1945 his name was on the list of sailors aboard the Robert F. Keller, a destroyer escort, when it sailed out of the Philippines for what turned out to be its last mission. Ten days later, his ship assisted in the sinking of the I-13, a submarine off the coast of Japan.

The Keller was part of the escort convoy when the aircraft carrier USS Bismark Sea was lost in a Kamikaze attack – the two US destroyers and three escort ships nearby managed to pick up 605 survivors over the next twelve hours. Those were facts Ray J. never mentioned. I had to do a little research. Sort of like Don’s story.

Don Spaulding was just a teenager when he enlisted, but he picked the US Army. His family lived within an afternoon’s car drive of Ray J.’s family, and the Robert Keller actually sailed into the Philippine Islands and the very strip of land where Spaulding was stationed. But Don wasn’t there anymore.

Japanese forces had taken the Philippines early on – and the US troops were ordered to surrender. What ensued has been called the Bataan Death March, but that was just the start of it. From his place of assignment at Clark Field, Don and his unit joined others as they were herded to a location where they could be transported to Japan.

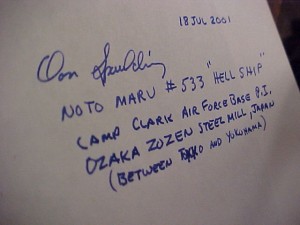

There were labor shortages among manufacturers, and the US prisoners of war were to be carried to Japan to work as slave laborers. There were 345 men taken from Clark Field. After the long march to Manila, they were loaded into the hold of a freighter called the Noto Maru.

In August of 1944, there were one-thousand-thirty-five prisoners jammed into the forward hold of the Noto Maru. The hatch covers were closed initially, and the heat was beyond belief. Bathrooms were simply buckets stuck against the wall. The POWs were given a cup of water and two rice portions a day. The young men lived in the cramped hold of the freighter Noto Maru for twelve days.

Years later, Don learned that a great many prisoner transports were unknowingly attacked by US ships – because they had every appearance of an enemy transport. At Moji, Japan, the prisoners were at last removed from the ship and loaded onto railway cars, having survived an attack and two torpedoes that ran deep.

Don Spaulding stayed on the train until it reached a point between Tokyo and Yokohama where he was to begin working at the Osaka Zōsen steel mill, producing equipment that would be used in the Japanese war effort. He spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, but many of his comrades were not so fortunate. Conditions were dire, the work was hard, and food was scarce.

Ray J. returned to Parsons and Don eventually found his way back to Tulsa.

Don Spaulding didn’t stay home for long. Almost unbelievably, he traveled to Texas and re-enlisted at Fort Sam Houston in 1946 and specifically requested to be assigned to the Pacific – the Hawaiian Department.

Years later, and back in Tulsa, Don was reminded of his comrades who shared the dark hold of that Japanese freighter bound for Japan, fellows from Company Three like Charles Ashcraft, Fred Bolinger, and Otha Johnson. His good buddy Alfred Sorensen. Pete Armijo, John Chesebrough and Juan De Luna. Don’s name was in there too – ironically – listed right beneath his friend Alfred.

The book was Brothers from Bataan. It tells the story of those brave men who lived an ordeal that the rest of us cannot even imagine. When it came into the shop, I noticed the signature and some cryptic notations. It wasn’t an author’s autograph, and it took a little investigating.

I learned what Noto Maru signified – a ship in the group of some two-dozen vessels referred to in later years as “Hell Ships,” the unmarked freighters that carried prisoners off to Japan.

Don Spaulding owned the book and already knew the information he wrote on the title page. I believe he wanted to make his mark on the wall, like many prisoners of war did. A simple, personal legacy intended for those who might come later. Many who carved their names into the walls of their prison cells did not have much time left. Don lived another eight years. He died in Tulsa in 2009.

His story is not so different from that of Louis Zamparini’s, the subject of the book Unbroken. Zamparini survived a plane crash in the ocean only to drift on a raft into Japanese-held islands. He also wound up working as a slave laborer.

The story of Ray J. – my father – is one that will never be known. Like Don, he was a young man who left home to serve the United States against aggressors, with no guarantee of returning. I can’t share Ray J.’s story, because I don’t know the full of it.

But I can share the tale of another young man from the Midwest as a measure of respect for their service, and as a token of my regret that it did not occur to me to express my pride and appreciation to my father – until I had missed my opportunity.

Better late than ever, I hear.

Proud of you, Pa.